FREE SPEECH HISTORY TIMELINE

Dive into a timeline covering the subjects of Clear and Present Danger. The timeline will expand as we travel through the history of free speech.

Free speech history

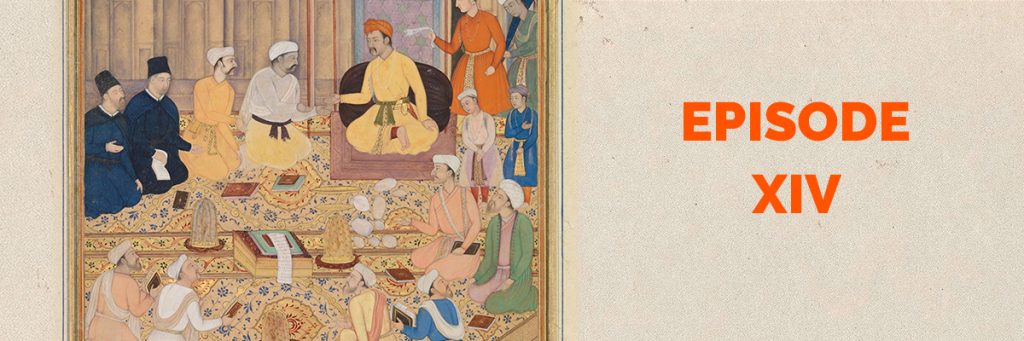

Episode XIV: ‘Universal Peace’ – Religious tolerance in the Mughal empire

Episode 14 leaves the West and heads to 16th and 17th Century India and the Mughal empire. In particular, the rule of Akbar the Great.

A century before John Locke’s “A Letter Concerning Toleration,” Akbar developed a policy of “Universal Peace” repudiating religious compulsion and embracing ecumenical debate. We’ll also discover why the history of the Mughal empire still tests the limits of free speech and tolerance in modern India. Among the questions tackled are:

- Why, how, and to what extent did Akbar abandon orthodox Islam for religious tolerance?

- How did religious tolerance in the Mughal empire compare to contemporary Europe?

- How did English travelers get away with openly blaspheming Muhammad, the Quran, and Allah?

- Was the emperor Aurangzeb really the uniquely intolerant villain that history has portrayed him as?

- Why do India’s current laws against religious insults hamper modern historians’ efforts at documenting events during the Mughal empire?

1556-1605: Akbar the Great

The Mughal Emperor Akbar is famous for his religious tolerance: He abolishes the Jizya tax on non-Muslims, allows forced converts to re-convert and invites priests of different faiths to discuss their religious believes. He even schools the Persian Shah ‘Abbas and the Spanish king Philip II on the values of tolerance.

‘Formerly I persecuted men into conformity with my faith and deemed it to be Islam. As I grew in knowledge, I was overwhelmed with shame.’

– Akbar the Great

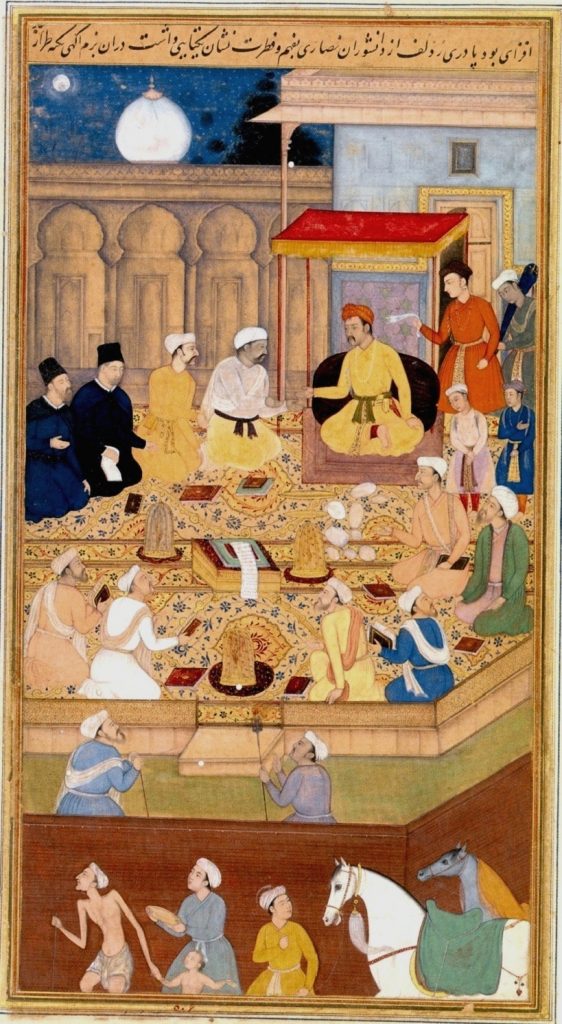

1658-1707: Aurangzeb

Aurangzeb reading the Qurʼān, unknown painter

The Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb is the spitting counter-image of his great-grandfather, Akbar. An orthodox muslim hardliner, he reimposes the Jizya on non-Muslim subjects, fires Hindu officials and has Hindu temples razed to the ground.

Episode XV: Paper-bullets and the forgotten martyrs of radical free speech

Episode 15 returns to Europe and formative events in 17th Century England, where a mostly forgotten group of radicals demand a written constitution guaranteeing free speech, liberty of conscience, and democracy. But who are the Levellers? What is the historical context of their radical demands and why are they crushed by their former allies?

1643: Licensing Order

The British parliament establishes pre-publication censorship in 1643, when it issues the Licensing Order. The Licensing Order moves Milton to write his famous argument for free speech, the Areopagitica. It is abolished in 1695.

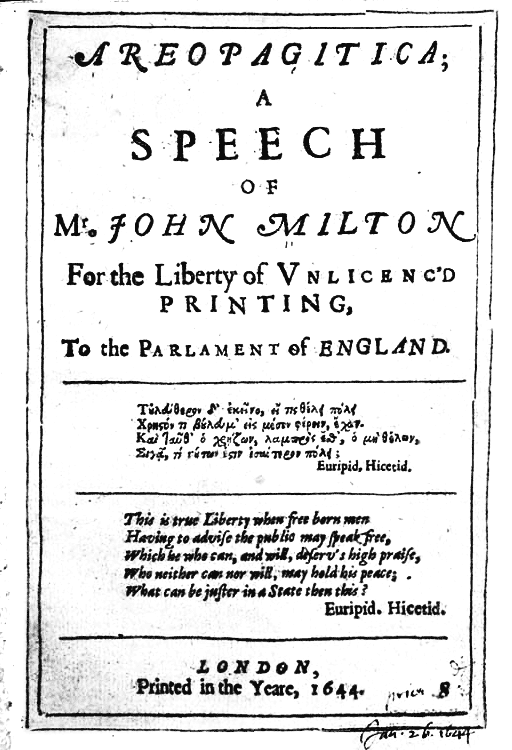

1644: John Milton’s Areopagitica

John Milton publishes Areopagitica, his famous argument for free speech, in 1644. According to Milton, the only way to reach the truth is by letting conflicting ideas meet.

The immidiate occassion of the text is the Licensing Act of 1643. Areopagitica has a limited impact on the parliament, but a big impact on the political thinkers of the Enlightenment.

“Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties.”

– John Milton, Areopagitica(1644)

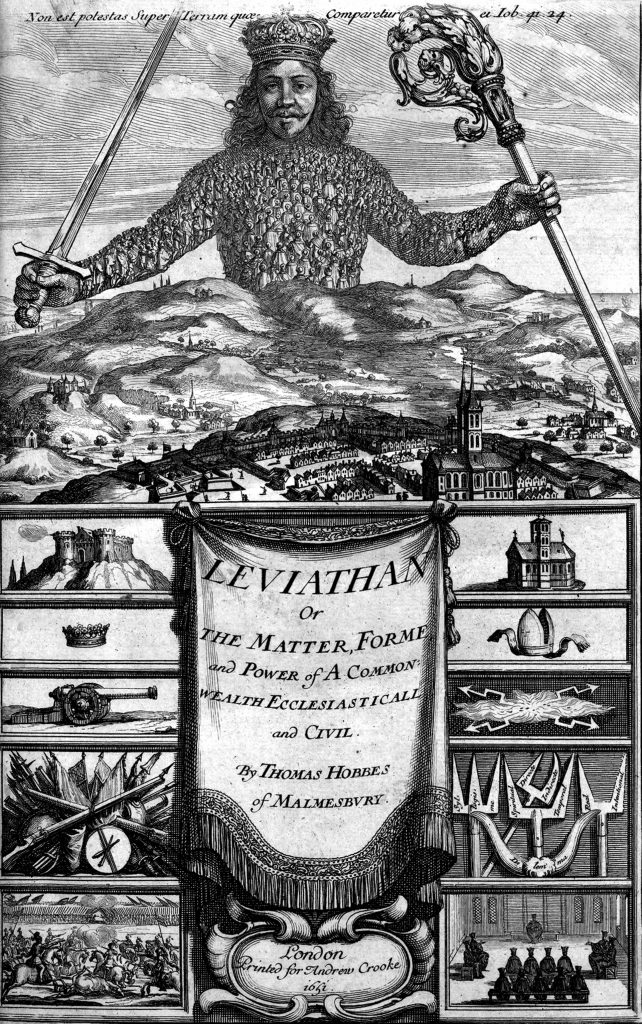

1651: Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan

The political thinker Thomas Hobbes is not a proponent of free speech or freedom of the press. In his greatest work, the Leviathan from 1651, he presents a number of arguments against press freedom. According to Hobbes, the sovereign should have absolute powers to censor dangerous opinions to ensure peace and prevent civil wars.

“… it is annexed to the sovereignty to be judge of what opinions and doctrines are averse, and what conducing to peace; and consequently, on what occasions, how far, and what men are to be trusted withal in speaking to multitudes of people; and who shall examine the doctrines of all books before they be published. For the actions of men proceed from their opinions, and in the well governing of opinions consisteth the well governing of men’s actions in order to their peace and concord. And though in matter of doctrine nothing to be regarded but the truth, yet this is not repugnant to regulating of the same by peace. For doctrine repugnant to peace can no more be true, than peace and concord can be against the law of nature. It is true that in a Commonwealth, where by the negligence or unskillfulness of governors and teachers false doctrines are by time generally received, the contrary truths may be generally offensive: yet the most sudden and rough bustling in of a new truth that can be does never break the peace, but only sometimes awake the war. For those men that are so remissly governed that they dare take up arms to defend or introduce an opinion are still in war; and their condition, not peace, but only a cessation of arms for fear of one another; and they live, as it were, in the precincts of battle continually. It belonged therefore to him that hath the sovereign power to be judge, or constitute all judges of opinions and doctrines, as a thing necessary to peace; thereby to prevent discord and civil war.”

– Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (1651) p. 164

1662: The Licensing of the Press Act

Satire from ‘Grub Street Journal’, London, 1732

The English Parliament issues “the Licensing of the Press Act” in 1662, two years after the restoration of Charles II. It bans the printing, selling and importation of “heretical seditious schismatical or offensive Bookes or Pamphlets” anywhere in the British Empire:

“… no person or persons whatsoever shall presume to print or cause to be printed either within this Realm of England or any other His Majesties Dominions or in the parts beyond the Seas any heretical seditious schismatical or offensive Bookes or Pamphlets wherein any Doctrine or Opinion shall be asserted or maintained which is contrary to Christian Faith or the Doctrine or Discipline of the Church of England or which shall or may tend or be to the scandall of Religion or the Church or the Government or Governors of the Church State or Common wealth or of any Corporation or particular person or persons whatsoever nor shall import publish sell or dispose any such Booke or Books or Pamphlets nor shall cause or procure any such to be published or put to sale or to be bound stitched or sowed togeather.”

– The Licensing of the Press Act (1662)

1415: The Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese conquer Ceuta in Morocco in 1415, turning the first sod in a soon-to-be global empire. They colonise Guinea-Bissau in 1474, Brazil in 1500, Mozambique in 1501, Goa in 1510, Malacca in 1511, Macau in 1557, Nagasaki in 1570 and Angola in 1575. Everywhere they go, they spread the Catholic faith.

1492: The Spanish Empire

Columbus stumbles on the American continent in 1492. A generation later, Spanish conquistadors subjugate the Aztecs, the Mayas and the Incas. Before long, Spain’s vast American empire stretches from New Mexico in the North to Argentina in the South.

Everywhere they go, the Spanish bring Catholic missionaries: 10 million native Americans are converted before 1550. The Franciscan missionaries raze native temples, confiscate sacred images and ban traditional games and dances. Women are instructed to cover their naked bodies, and chastity and monogamy are enforced by the whip. In the words of a Franciscan missionary, conversion has to be “reinforced by the fear and respect which the Indians have for the Spaniards.”

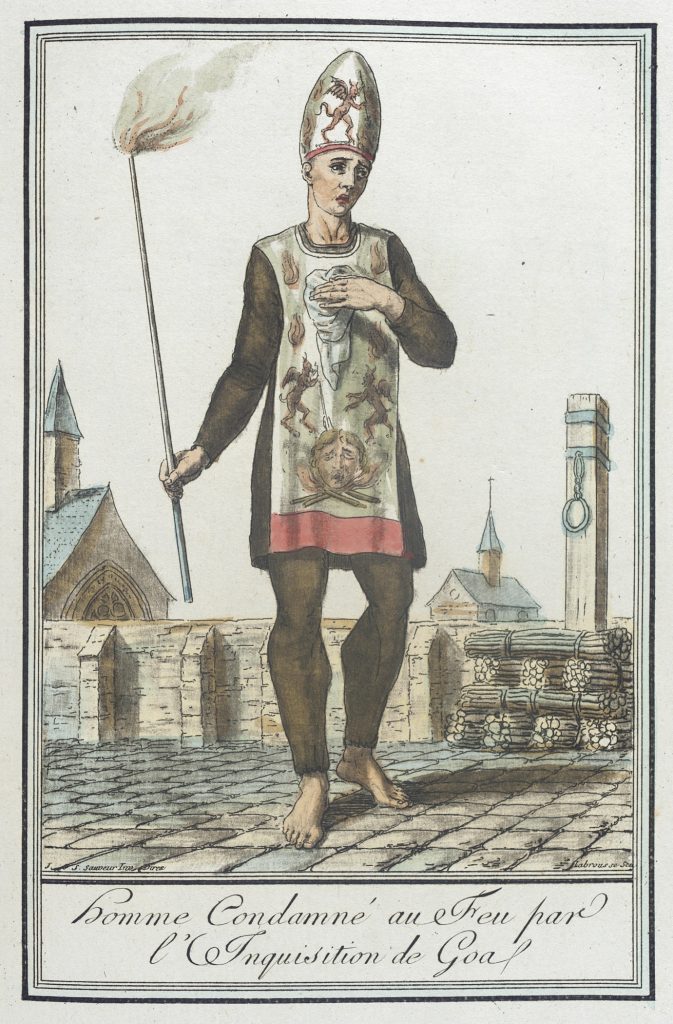

1536: The Portuguese Inquisition

Man about to be burnt at the stake in Goa (Jacques Grasset de Saint-Sauveur, c. 1797, Public Domain)

The Portuguese Inquisition is launched by papal bull in May 1536. Five years later, king João III extends the Inquisition to the cover the whole Portuguese Empire. Until 1821, the Inquisition investigates more than 50,000 trials and executes around 2,000. The most serious crimes include Judaism, Lutheranism, Islam, heretical opinions, witchcraft and bigamy.

An independent tribunal is set up in Goa in 1560: The massive institution covers all the Eastern colonies from Sofala on Africa‘s East Coast to Malacca in Malaysia. Brazil is under the jurisdiction of the central tribunal in Lisbon.

1570: The Spanish Inquisition in America

Auto-da-fé in Lima (Pancho Fierro, 1807-1879. Public Domain)

In 1570, the Spanish Inquisition opens two independent tribunals in America: One in Mexico City (New Spain) and one in Lima (Peru). A third tribunal opens in Cartagena (Columbia) in 1611. By 1700, the tribunal in Lima has investigated 1176 cases and convicted 46 to death. The tribunal in Mexico City has investigated 950 cases and convicted 59 to death. The most frequently prosecuted crimes are heresies and blasphemies, closely followed by Judaism. Protestantism and Islam are also illegal.

Sancho de Aldana is convicted of blasphemy in 1572. He is sentenced to declare his crimes in public, naked to the waist, with a gag in his mouth and a candle in his hand. He is then paraded through the streets of Mexico City on a mule before receiving 100 lashes and being kicked out of Mexico for four years.

1571: Censorship in Spanish America

America’s first printing office opens in Mexico City in 1539. The Church keeps printers on a tight leash: Novels are forbidden all together and a strict index of forbidden books is enforced.

In 1571, Mexico’s new Inquisitor General launches a massive book purge – even the Franciscans are caught with illegal books in their libraries.

Episode XVIII: Colonial Dissent – Blasphemy, Libel and Tolerance in 17th Century America

In 17th Century colonial America, criticizing the government, officials or the laws is punishable as seditious libel. It can result in the cropping of ears, whippings, boring of the tongue and jail time. Religious speech is also tightly controlled: Blasphemy is punishable by death in several colonies and religious dissenters such as Quakers are viciously persecuted in Puritan New England.

But despite the harsh climate of the 17th century, the boundaries of political speech and religious tolerance are significantly expanded.

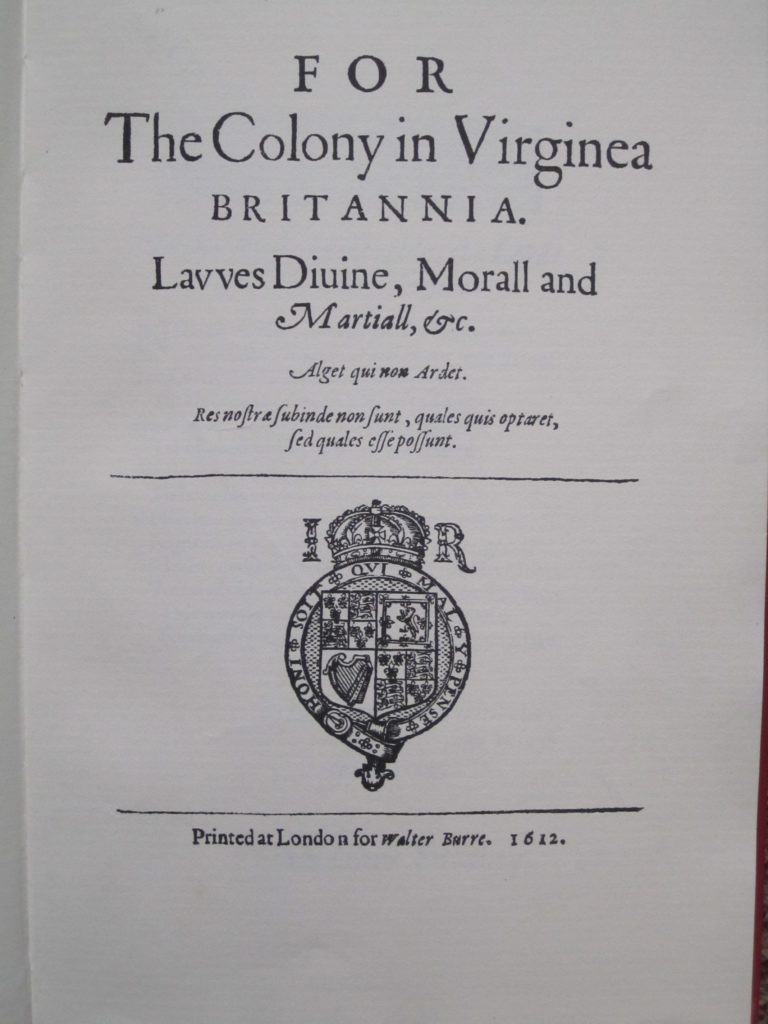

1612: Dale’s code

Title page of Dale’s Code, 1612

In 1612, Virginia’s first governor Thomas Dale issues a long list of offenses known as Dale’s Code or Dale’s Laws. The code punishes speech and thought crimes like lèse-majesté, blasphemy, heresy and lying by death.

2 That no man speake impiously or maliciously, against the holy and blessed Trinitie, or any of the three persons, that is to say, against the knowne Articles of the Christian faith, upon paine of death

3 That no man blaspheme Gods holy name upon paine of death, or use unlawful oathes, taking the name of God in vaine, curse, or banne, upon paine of severe punishment for the first offence so committed, and for the second, to have a bloodkin thrust through his tongue, and if he continue the blaspheming of Gods holy name, for the third time so offending, he shall be brought to a martial court, and there receive censure of death for his offence.

4 No man shall use any traiterous words against his Majesties Person, or royall authority upon paine of death

5 No man shall speake any word, or do any act, which may tend to the derision, or despight of Gods holy word upon paine of death…

– Dale’s Code, 1612

1641: The Massachusetts Body of Liberties

The colony of Massachusetts issues the Body of Liberties in 1641. With explicit inspiration from the Old Testament, the law code punishes heresy, blasphemy and homosexuality by death. Attempts at “alteration and subversion of our frame of politie or Government fundamentallie” is also punishable by death.

“94. Capital Laws

(Deut. 13. 6, 10. Deut. 17. 2, 6. Ex. 22.20)

If any man after legall conviction shall have or worship any other god, but the lord god, he shall be put to death.

…

(Lev. 24. 15,16.)

If any person shall Blaspheme the name of god, the father, Sonne or Holie Ghost, with direct, expresse, presumptuous or high handed blasphemie, or shall curse god in the like manner, he shall be put to death.

…

(Lev. 20. 13.)

If any man lyeth with mankinde as he lyeth with a woeman, both of them have committed abhomination, they both shall surely be put to death.

…

If any man shall conspire and attempt any invasion, insurrection, or publique rebellion against our commonwealth, or shall indeavour to surprize any Towne or Townes, fort or forts therein, or shall treacherously and perfediouslie attempt the alteration and subversion of our frame of politie or Government fundamentallie, he shall be put to death.

Read the full text here.

Episode XX: The Seeds of Enlightenment

In 1685, the Sun King Louis XIV revokes the Edict of Nantes and initiates a policy of religious persecution of French Protestants. In England, the Catholic James II assumes the throne to the horror of the Protestant majority in Parliament. From their exiles in the Dutch Republic, the French philosopher Pierre Bayle writes his groundbreaking defense of religious tolerance “Commentaire Philosophique”, and John Locke the original Latin version of his Letter Concerning Toleration. In this episode, we trace the seeds of the Enlightenment covering events in France, the Dutch Republic, and England.

1670: Spinoza’s Tractatus theologico-politicus

Baruch Spinoza c. 1665 (Public Domain)

In 1670, the philosopher Baruch Spinoza publishes his controversial Tractatus theologico-politicus anonymously. The book argues for libertas philosophandi – the “freedom to philosophize” – and reads the Bible with a critical eye.

“In a Free Commonwealth it should be lawful for every Man to think what he will, and speak what he thinks”

– Baruch Spinoza: Tractatus theologico-politicus (1670)

The book is too controversial, even for the tolerant Dutch. Spinoza’s patron Jan de Witt is assassinated in 1672. The same year, a viral anonymous pamphlet calls the Tractatus a “book forged in hell by the renegade Jew together with the Devil”.